During my last trip to England, I divided my time between Gloucestershire and West Sussex. While staying in Cirencester, I visited wondrous places like Gloucester Cathedral and the picturesque Cotswolds town of Painswick. In Sussex, I couldn’t resist another tour of Arundel Castle, as well as trips to Brighton and London. While Sussex offers many places to visit, it was my first time traveling to Fishbourne to see its impressive Roman Palace.

During my day trip to the ancient ruins, I stopped by another Roman ruin at Bignor Roman Villa. Riddled with Roman walls, mosaics, and old structures, I find the United Kingdom a fascinating place to visit. While I have explored many of Britain’s abandoned castles, I was intrigued to learn about the process of excavation.

Where Is Fishbourne Roman Palace?

- Location: Roman Way, Chichester, West Sussex | Open: Daily 10 am to 4 pm (times may vary during Covid-19)

Located in Fishbourne, near Chichester, visitors can easily find this structure off the A27 west of the Bognor Regis. Positioned on a dead-end street, I noted ample, free parking, which was relatively empty when I arrived.

Without a car, the Fishbourne train station nearby provides access to the town. So, if you’re staying in London, the Roman ruins make a great day trip from the capital by train. From the station, it’s an easy five-minute walk to the Palace. Should you belong to the Sussex Archaeological Society, members pay no entrance fee. Otherwise, the Villa charges visitors a nominal GBP 10.00 for adults, GBP 5.20 for children 5 to 16 years, and GBP 9.60 for seniors. Children under five are free.

The History Of Fishbourne Palace

Arriving at the Fishbourne Palace, I stepped back in time and explored the largest known Roman building in Northern Europe. Discovered by accident in 1960, it took years of careful excavation to gently uncover the thousands of artifacts.

Estimated to have been constructed in AD 75, I was astonished to see the fantastic condition of the palace floors, given their age. Believed to be built as a military base and the home of Tiberius Claudius Togidubnus (also known as Cogidubnus), the colossal Palace succumbed to fire around 280 AD. At the time of the fire, the building was under renovation. But due to the catastrophic event, it was never completed. After the fire, the damage was irreparable, so the ruins were abandoned and left to the elements of weather.

In size, it mirrors Nero’s Golden House located in Rome. At the site, I watched an informative film showing what the Palace looked like in its prime. Constructed as a square with four wings and surrounding a formal courtyard, the villa resembles a palatial residence fit for royalty. Watching the film and seeing a scale model of the complete Palace, I could only imagine the opulence of this place thousands of years ago.

The north and east wings housed suites that encompassed smaller courtyards. Archaeologists have excavated the north wing, which visitors can enjoy today.

What To See At Fishbourne Roman Palace?

Much of the excavated site remains undercover to protect it from the continuous elements of weather. Browsing the small-scale artefacts, I viewed ancient coins, pottery, and everyday objects such as knives and iron keys.

The fire melted much of the glass windows and shattered pottery items. However, the archaeologists reassembled some of the pottery items for display. During excavation, archaeologists uncovered the remains of pagan burials, and some are on display at the Palace.

Initially, the Palace had 100 rooms, and during my visit, I could view a recreated room, complete with a mosaic floor and painted plaster walls. The residents built their furniture from wood, but after 2,000 years, none has survived.

In a cavernous room, the 2,000-year-old North Wing mesmerized me with its incredible floors that have stood the test of time. While the walls are gone, the stone footings and mosaic floors show the layout of the Palace. I marveled at the visitors’ centre, which was ingeniously designed with railing walkways over the original corridors, protecting the ancient artefacts from modern-day shoes.

The Mosaics

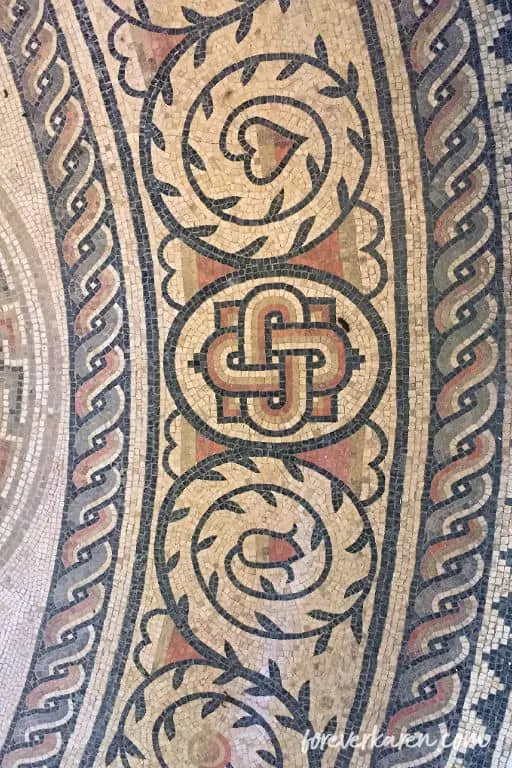

With wide pathways, each visitor can admire the intricate mosaics below without the risk of overcrowding. These mosaic floors ranged in size from small sections to almost entire rooms. It’s interesting to note; that this is the most extensive collection of mosaics in the country. Admiring the designs, I observed some were very different from others.

Mosaicists created many of the first tiled floors from black and white stone, and the designs were relatively simple. Italian mosaicists created these designs since local artisans hadn’t perfected the skill. The supplies were local, though, making use of the abundance of limestone and chalk.

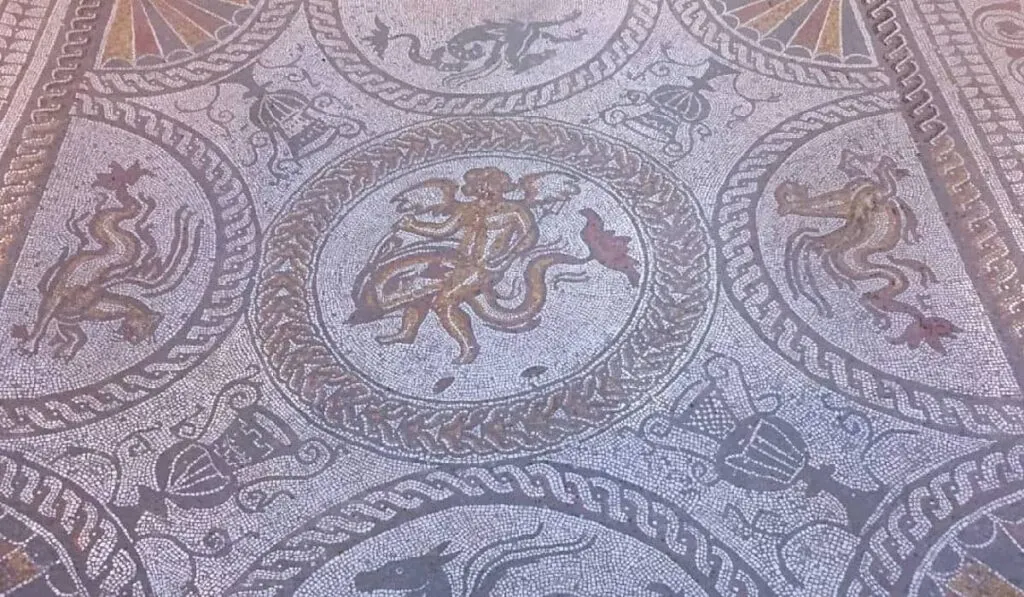

A century later, artisans laid new mosaics over the top, which contrasted with the original two-tone geometrics. Many of these were vivid in colour and incorporated elaborate motifs that are simply stunning, although some of the inlaid work lacked the artistry of the originals.

The second-century Cupid on a Dolphin Mosaic (seen at the top of this article) was a stand-out mosaic for me. The design positions Cupid and the Dolphin in the centre, surrounded by vases, winged sea horses, and bordered by a beautiful rope design. The design changed to create a “doormat” to welcome guests at its entrance. Within the scrolling border, a single blackbird acts as the artist’s signature.

The newer mosaics feature coloured stones of red, yellow, and grey. However, much of the hues have faded due to the massive fire. As impressive as this collection of mosaics is, I was astonished to learn that most of the Roman Palace remain unexcavated under roadways and residential homes. Although archaeologists discovered more mosaics in the west wing, they reburied them to protect them from the elements.

Roman Hypocaust System

One of the things that fascinated me at the Fishbourne Roman Palace was its Roman hypocaust system. The hypocaust or underfloor heating system provided a way to heat the palace through furnace gases funneled into chambers under the floor.

The basement hypocaust consisted of towers of stone set two feet apart, allowing for open spaces. A cement floor or larger stone was laid on top, enclosing the chamber below. The mosaics were laid on the cement layer, completing the room’s floor. Heated gases from nearby furnaces flowed into the underfloor chamber, creating what we now call in-floor heating.

Throughout the years, the hypocaust underwent renovations and the addition of interiors baths.

Fishbourne Palace Gardens

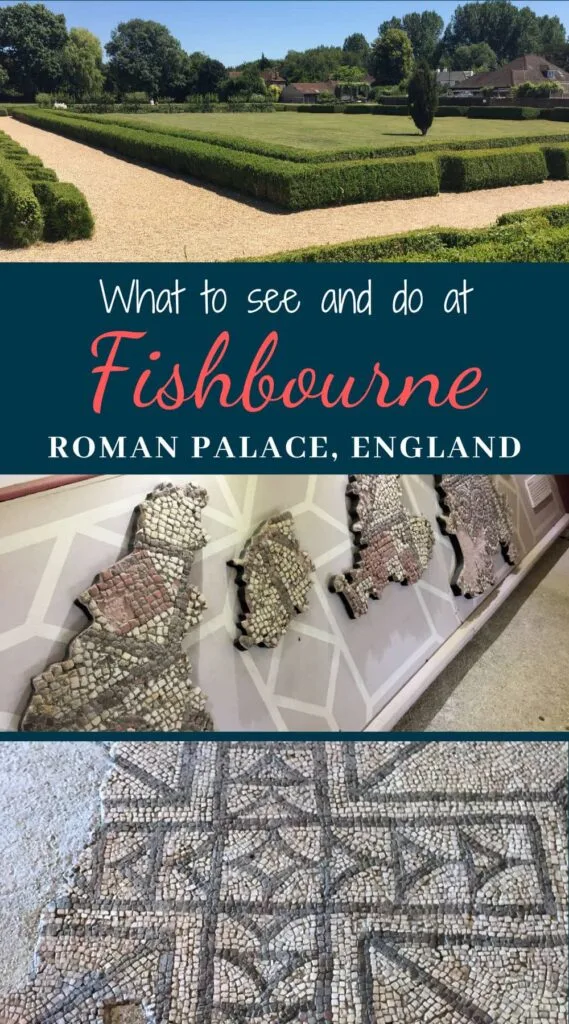

Outside, the central courtyard replicates the original design of a large grassed area bordered by boxwood hedging. Its simple design is far less stately than the Palace itself. A 40-foot-wide central pathway leads to a flight of stairs in front of the audience chambers. In the centre, a square stone marks the base of where a statue stood.

Scattered on the grounds, stone foundations show the position of the other building’s wings. Excavated piping shows the roman channeled water into the villa. Since the interior mosaics included various roses, historians believe they may have been planted in the formal gardens.

Adjacent to the courtyard, a kitchen garden suggests the residents grew their food in the rich soil. In another building, the storeroom houses thousands of uncovered artefacts that have yet to be examined and cleaned up for display.

After an enjoyable visit to Fishbourne Palace, I also visited another nearby Roman Villa, just 16-1/2 miles away.

Bignor Roman Villa

- Location: Bignor, West Sussex | Open: Daily 10 am to 5 pm (times may vary during Covid-19)

Driving the winding road to Bignor Roman Villa, I felt like I was in the middle of nowhere. Located in the South Downs, the historic structure is surrounded by the beautiful West Sussex countryside. Visitors are best to arrive by car since the nearest train station is in Amberley, over three miles away.

Arriving at the Villa, I saw 2,000-year-old stone columns in the field where the Villa once stood. Nearby, thatched-roof cottages housed the artefacts and preserved mosaic floors.

Admission to see the artefacts costs GBP 6.50 for adults, GBP 4.50 for seniors, and GBP 3.50 for children under 16 years.

What To See At Bignor Roman Villa

Like the Palace in Fishbourne, the Romans built Bignor Roman Villa as a square around a central courtyard. Smaller than Fishbourne Palace, it’s believed the initial Villa had 65 rooms. In 1811, a farmer, George Tupper, discovered the Villa while plowing a field. A few years later, the Tuppers opened the Villa to the public. Today, the Tupper family still owns the Roman structure at Bignor, which dates from the mid to late 2nd century.

Inside, a small-scale model shows what the Villa looked like at 2,000 years old. Artefacts on display include pieces of pottery, animal bones, and fragments of mosaic floors. In 1996, archaeologists found an infant’s remains on the site. Romans buried their babies close to the settlement for unknown reasons, but they laid adults to rest elsewhere.

The Bignor Mosaics

Browsing the thatched buildings, I admired the mosaic floors noting that their colours were more vivid than those found at Fishbourne. On display in the north corridor, I viewed the longest mosaic in England at 24 metres or almost 79 feet. During the third century, this original mosaic pavement measured 70 metres or 230 feet. At the end of the corridor, a black dolphin with its creator’s signature adorns the floor.

The Villa’s centre houses the Ganymede mosaic, first discovered by George Tupper. The oversized design features a hexagon water basin in the floor. It acted as a focal point but also as decoration. A lead pipe under the floor supplied the water.

I admired the Venus and Cupid Gladiator mosaic in another building, the centrepiece of the winter dining room. A single cupid floats innocently at one end, while the opposite end features a strip of fighting gladiators. Above the fighters, long-tailed birds surround the head of Venus.

I’d imagined that during its creation, this was a magnificent floor. Even centuries later, the remarkable mosaic astonished me, and I found it hard to believe it was 2,000 years old.

Today, the centre of the floor has collapsed, allowing me to view the same underfloor heating system seen at Fishbourne Palace. Nearby, a hypocaust flue indicates where the heated gases escaped, preventing the inhabitants from getting carbon monoxide poisoning.

The final building housed a magnificent floor mosaic of Medusa, a focal point of the bathhouse. With Medusa featured in the centre, the design radiated outwards with swirls and ropes of red, yellow, grey, black, and white tiles. Admiring the composition, I couldn’t imagine how long it would have taken to create such a masterpiece.

The Grounds

Outside, a large “Frigidarium” or cold bath would have serviced all those who lived in the Villa. With steps leading into the tub, Romans would have played, talked, and met friends here. During Roman times, there was no soap. Instead, bathers rubbed olive oil on their skin and scrapped it off with a curved blade instrument called a strigil.

Final Thoughts

If you’re fascinated by British history and want to see the finest preserved floor mosaics in England, these two venues are a must. While many visitors flock to Bath to admire the Roman ruins, most don’t know these West Sussex gems.

Located close together, I managed to visit them both in one day, spending adequate time at each place. While I didn’t know what to expect, I learned a lot about Roman heating systems, and I left mesmerized by the fantastic mosaics.

Happy travels ~ Karen